John Pender's War

John Pender's War

Threat of war was looming at this time and come August with Germany overrunning 'plucky little Belgium' Britain was at war. John along with thousands of his age group rushed to join the army. On the 27th of August 1914 John enlisted in the Cameron Highlanders Regular Army. He was posted that same day to the Camerons' Depot at Invergordon and the following day was posted to the 6th battalion; and almost immediately the battalion was sent to Basingstoke in Hampshire for basic training. Along with his contemporaries in the Church bible classes in Paisley, John had been a staunch member of the Boys' Brigade, which in those days had regular drill with wooden rifles. John's rank of Staff Sergeant in the B.B. was obviously instrumental in his being, at the beginning of February 1915, appointed to the rank of Lance corporal. After basic training and general toughening-up around the Basingstoke area, the battalion marched to Chiseldon near Swindon in two days at the end of April. Further training here included twenty-four mile route marches as well as Battalion exercises.

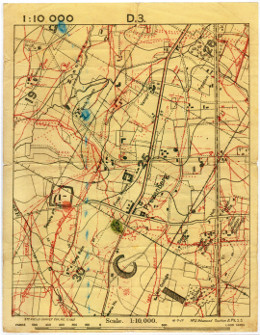

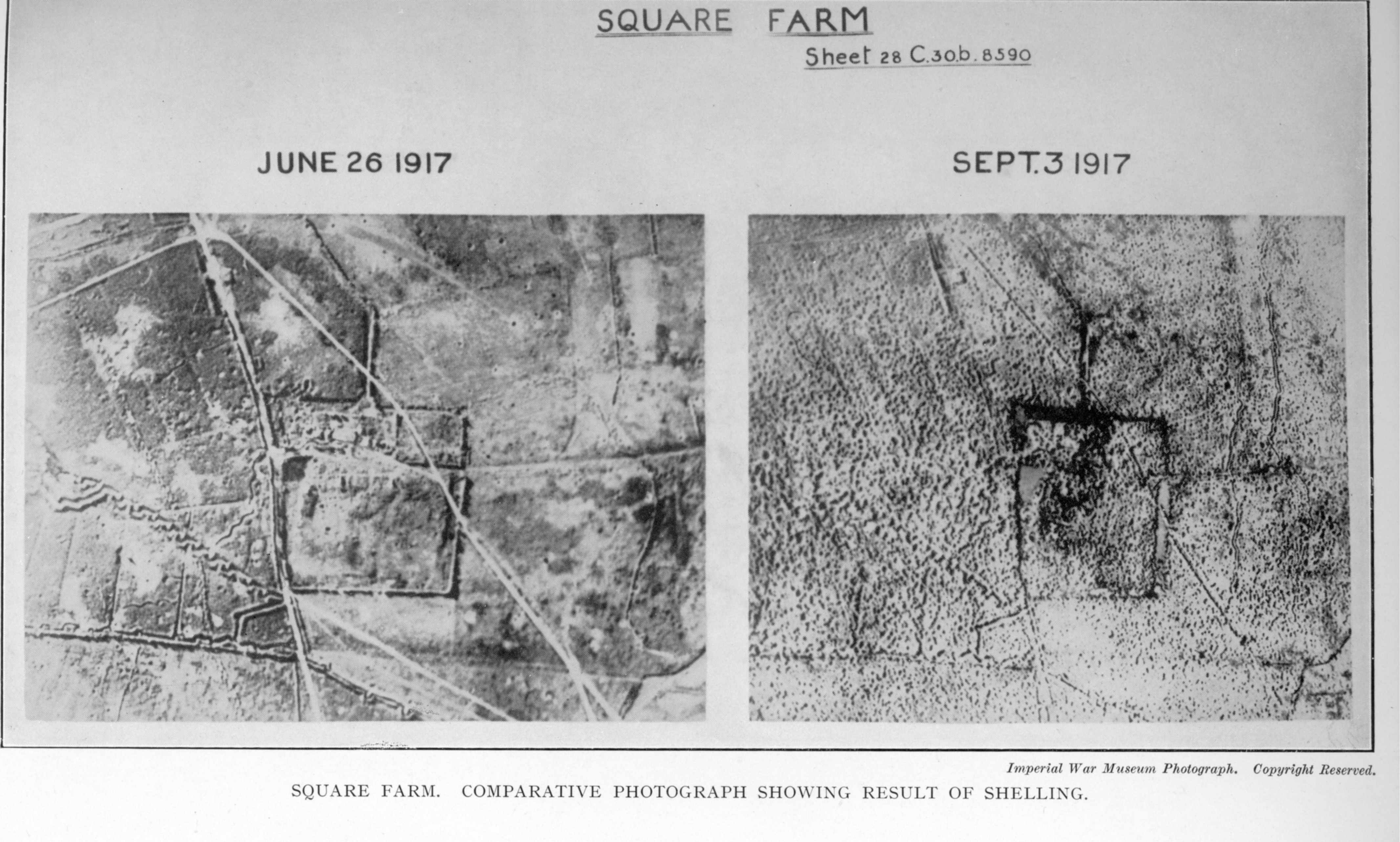

In July the battalion moved to Folkestone and on July 10th set foot on French soil Lance corporal Pender trained as a signaller, and one of his main jobs was to lay telephone cables between the various command posts on the battlefield. This was a never-ending job as the enemy shells were continually breaking the wires, so he and his comrades were kept very busy. He led a charmed life on the battlefield and was promoted Corporal on the 6th January 1917.

In July of that year his luck ran out. During the Third battle of Ypres, on the 31st of that month he was out at his usual task of mending the communication cables when he was shot in the shoulder by a sniper. He fell to the ground and his mate of the day, Wee Hannah, a small highlander who though Liverpool born was now from Maryhill in Glasgow, came running over to help him. The sniper's aim was better the second time and Wee Hannah fell dead over his friend Jock. John used to tell how he lay there for hours under Wee Hannah’s body until darkness fell when he was able to struggle back to his own trenches and the tender care of the stretcher-bearers. (For some more information about Fred Hanna click here).

This extract from "The War History of the Sixth (Service) Battalion, Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders" page 69:

----"Telephonic communication was established between the reserve trench and Battalion headquarters with an intermediate post at Bullet trench. This line, extending over some 2500 yards of ground was maintained entirely by battalion signallers and linesmen for forty-eight hours. Breaks constantly occurred under shellfire, but these were immediately repaired by the linesmen in spite of heavy artillery activity, machine-gun fire and sniping. Signallers and linesmen at all times had a strenuous and dangerous job, which they carried out with great bravery. The lines being laid in the open were easily cut and the men were constantly being called on by day and night to go out, often during heavy shelling, to find and repair the break"

Dad used to talk of going out at night with one other man to find and repair the break, both holding on to the wire. When the man in front lost the end he called to the rear man to halt holding the broken end. The job of the front man was then to make a wide sweep ahead to find the other end of the break (not an easy job in the pitch dark). On finding that end he would have to splice on a spare length of wire to that end and then creep back to find his mate still holding the first end and reconnect the line. Most of these "men" were only in their 'teens or early twenties.

It was almost two weeks after his being shot that his mother received notice from the Infantry Record Office in Perth that her son had been wounded and was admitted to 10th Stationary Hospital, St Omer, on the 1st of August. The nature of the wound was given as Gunshot: Shoulder, Severe. John's age was 20 years and 8 months. It was certainly a 'Blighty' wound because he was posted to Depot on the 14th of August. It was not until the 18th of October that John was posted to the 3rd Battalion, which I believe, was stationed in Ireland at that time.

On the 21st of January 1918 he was posted to the 2nd Battalion and sent out to Salonica via France and Italy by boat and train. On the 18th of September his Mother received a second letter from the Records Office in Perth, this time telling her that the Army Council regretted to inform her that John had been admitted to No. 8 General Hospital, Salonica on the 3rd of that month. The nature of the wound was given as "Gunshot Face". I was never able to discover if John managed to write and beat that intimation home, or whether his Mother received that letter from the army out of the blue. What a shock she would have had, and what would her thoughts of disfigurement have been.

This was another of Dad's stories of the War. On the 2nd of September he was just sitting having a quiet smoke with his mates when an enemy shell exploded close by. John felt a sting on his cheek and put his hand up to his face. On looking at his hand he found that he was bleeding and realised that he had been scratched with a small piece of shrapnel or broken stone. He thought no more about it apart perhaps from thinking that he had had a lucky escape. However, shortly after, his Officer noticed John's bleeding cheek and ordered him to go and get it dressed, presumably to ward off the possibility of tetanus, which was an occupational disease on the battlefield. It seemed that the Army system could not cope with slight scratches and having had a wound reported and dressed the whole Administrative Machinery swung into action regardless of the possible consequences at home.

That is all I can recall of John's adventures in the War. The Armistice was declared on the 11th of November, but John wasn't posted back to Depot in Scotland from Salonica till 1st of February 1919, and on the 25th of March 1919 he was transferred to Class Z Army Reserve, which meant effectively he was once more a civilian. One thing he did bring back from Salonica was the Malaria virus, which for years up till the second war would strike him at least once a year. I have memories of him coming home from work ill and shivering. Mum would run a hot mustard bath for him and then pack him into bed tucked up with hot water bottles to sweat off the fever. I have no recollection of how long each of these bouts lasted though I know they made him very ill. Once home John lost

little time in returning to Campbell & Calderwood's to renew his interrupted apprenticeship